How to love a green bunny? The use of genetics in art.

"The human direct influence on dog´s evolution goes back at least 15.000 years and after centuries of natural selective breeding, a turning point in human breeding of dogs took place in 1859, when the first exhibition of dogs prompted appreciation for their unique visual appearance. The search for visual consistency and for new breeds led to the concept of pure breed and to the formation of different groups of founding dogs. The practice is with us today and is responsible for many of the dogs we see in homes everywhere. The results of indirect genetic control of dogs by breeders are proudly expressed on the pages of the canine trade press. A quick look at the marketplace reveals ads for bulldogs "engineered for protection," mastiffs with a "careful genetic breeding program," dogos with an "exclusive bloodline," and Dobermans with a "unique genetic blueprint." Breeders aren't writing the genetic code of their dogs yet, but they are certainly reading and recording it. The American Kennel Club, for example, offers a DNA Certification Program to settle questions of purebred identification and parentage.

"The human direct influence on dog´s evolution goes back at least 15.000 years and after centuries of natural selective breeding, a turning point in human breeding of dogs took place in 1859, when the first exhibition of dogs prompted appreciation for their unique visual appearance. The search for visual consistency and for new breeds led to the concept of pure breed and to the formation of different groups of founding dogs. The practice is with us today and is responsible for many of the dogs we see in homes everywhere. The results of indirect genetic control of dogs by breeders are proudly expressed on the pages of the canine trade press. A quick look at the marketplace reveals ads for bulldogs "engineered for protection," mastiffs with a "careful genetic breeding program," dogos with an "exclusive bloodline," and Dobermans with a "unique genetic blueprint." Breeders aren't writing the genetic code of their dogs yet, but they are certainly reading and recording it. The American Kennel Club, for example, offers a DNA Certification Program to settle questions of purebred identification and parentage."If the creation of dogs has long historical roots, more recent but equally integrated into our daily experience is our use of hybrid living organisms. Domestic ornamental plants and pets thus invented are already so common that one rarely realizes that a loved animal or a flower offered as a sign of affection are the practical results of concerted scientific effort by humans. Hybrid Teas, for example are the typical roses found at the Florist Shop -- the classic image of the rose. The first Hybrid Tea was 'La France', raised by Giullot in 1867. A cherished companion such as the Catalina macaw, with its fiery orange breast and green-and-blue wings, does not exist in nature. Aviculturists mate blue-and-gold macaws with scarlet macaws to create this beautiful hybrid animal.

"This is not at all surprising, considering that cross-species hybrid creatures have been part of our imaginary for millennia. In Greek mythology, for example, the Chimera was a fire-breathing creature represented as a composite of a lion, goat, and serpent. Sculptures and paintings of chimeras, from ancient Greece to the Middle Ages and on to modern avant-garde movements, inhabit museums worldwide. Chimeras, however, are no longer imaginary; today, nearly 20 years after the first transgenic animal, they are being routinely created in laboratories and are slowly becoming part of the larger genescape. Some recent scientific examples are pigs that produce human proteins, plants that produce plastic, and goats with spider genes designed to produce a strong and biodegradable fabric. While in ordinary discourse the word "chimera" refers to any imaginary life form made of disparate parts, in biology "chimera" is a technical term that means actual organisms with cells from two or more distinct genomes. A profound cultural transformation takes place when chimeras leap from legend to life, from representation to reality.

"The result of transgenic art processes must be healthy creatures capable of as regular a development as any other creatures from related species. Ethical and responsible interspecies creation will yield the generation of beautiful chimeras and fantastic new living systems, such as plantimals (plants with animal genetic material, or animals with plant genetic material) and animans (animals with human genetic material, or humans with animal genetic material).

"The patenting of new animals created in the lab and of genes of foreign peoples are particularly complex topics - a situation often aggravated, in the human case, by the lack of consent, equal benefit, or even understanding of the processes of appropriation, patent, and profit on the part of the donor. Since 1980 the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) granted several transgenic animal patents, including patents for transgenic mice and rabbits. Recently the debate over animal patents has broadened to encompass patents on genetically engineered human cell lines and synthetic constructs (e.g., "plasmids") incorporating human genes.

"Every living organism has a genetic code that can be manipulated, and the recombinant DNA can be passed on to the next generations. The artist literally becomes a genetic programmer who can create life forms by writing or altering this code. With the creation and procreation of bioluminescent mammals and other creatures in the future, dialogical interspecies communication will change profoundly what we currently understand as interactive art. These animals are to be loved and nurtured just like any other animal.

"The use of genetics in art offers a reflection on these new developments from a social and ethical point of view. It foregrounds related relevant issues such as the domestic and social integration of transgenic animals, arbitrary delineation of the concept of "normalcy" through genetic testing, enhancement and therapy, health insurance discrimination based on results of genetic testing, and the serious dangers of eugenics.

"This is where art can also be of great social value. Since the domain of art is symbolic even when intervening directly in a given context, art can contribute to reveal the cultural implications of the revolution underway and offer different ways of thinking about and with biotechnology. Transgenic art is a mode of genetic inscription that is at once inside and outside of the operational realm of molecular biology, negotiating the terrain between science and culture. Transgenic art can help science to recognize the role of relational and communicational issues in the development of organisms. It can help culture by unmasking the popular belief that DNA is the "master molecule" through an emphasis on the whole organism and the environment (the context). At last, transgenic art can contribute to the field of aesthetics by opening up the new symbolic and pragmatic dimension of art as the literal creation of and responsibility for life.

""Alba", the green fluorescent bunny, is an albino rabbit. This means that, since she has no skin pigment, under ordinary environmental conditions she is completely white with pink eyes. Alba is not green all the time. She only glows when illuminated with the correct light. When (and only when) illuminated with blue light (maximum excitation at 488 nm), she glows with a bright green light (maximum emission at 509 nm). She was created with EGFP, an enhanced version (i.e., a synthetic mutation) of the original wild-type green fluorescent gene found in the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria. EGFP gives about two orders of magnitude greater fluorescence in mammalian cells (including human cells) than the original jellyfish gene.

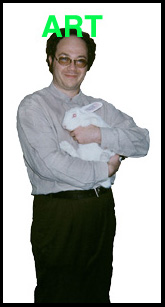

"The first phase of the "GFP Bunny" (Green Fluorescent Protein ) project was completed in February 2000 with the birth of "Alba" in Jouy-en-Josas, France. Alba's name was chosen by consensus between my wife Ruth, my daughter Miriam, and myself. The second phase is the ongoing debate, which started with the first public announcement of Alba's birth, in the context of the Planet Work conference, in San Francisco, on May 14, 2000. The third phase will take place when the bunny comes home to Chicago, becoming part of my family and living with us from this point on.

"As a transgenic artist, I am not interested in the creation of genetic objects, but on the invention of transgenic social subjects. In other words, what is important is the completely integrated process of creating the bunny, bringing her to society at large, and providing her with a loving, caring, and nurturing environment in which she can grow safe and healthy.

"This integrated process is important because it places genetic engineering in a social context in which the relationship between the private and the public spheres are negotiated. In other words, biotechnology, the private realm of family life, and the social domain of public opinion are discussed in relation to one another. Transgenic art is not about the crafting of genetic objets d'art, either inert or imbued with vitality. Such an approach would suggest a conflation of the operational sphere of life sciences with a traditional aesthetics that privileges formal concerns, material stability, and hermeneutical isolation. Integrating the lessons of dialogical philosophy and cognitive ethology, transgenic art must promote awareness of and respect for the spiritual (mental) life of the transgenic animal.

"The word "aesthetics" in the context of transgenic art must be understood to mean that creation, socialization, and domestic integration are a single process. The question is not to make the bunny meet specific requirements or whims, but to enjoy her company as an individual (all bunnies are different), appreciated for her own intrinsic virtues, in dialogical interaction.

"One very important aspect of "GFP Bunny" is that Alba, like any other rabbit, is sociable and in need of interaction through communication signals, voice, and physical contact. As I see it, there is no reason to believe that the interactive art of the future will look and feel like anything we knew in the twentieth century.

"Throughout the twentieth century art progressively moved away from pictorial representation, object crafting, and visual contemplation. Artists searching for new directions that could more directly respond to social transformations gave emphasis to process, concept, action, interaction, new media, environments, and critical discourse. Transgenic art acknowledges these changes and at the same time offers a radical departure from them, placing the question of actual creation of life at the center of the debate. Undoubtedly, transgenic art also develops in a larger context of profound shifts in other fields. Throughout the twentieth century physics acknowledged uncertainty and relativity, anthropology shattered ethnocentricity, philosophy denounced truth, literary criticism broke away from hermeneutics, astronomy discovered new planets, biology found "extremophile" microbes living in conditions previously believed not capable of supporting life, molecular biology made cloning a reality.

"Transgenic art acknowledges the human role in rabbit evolution as a natural element, as a chapter in the natural history of both humans and rabbits, for domestication is always a bidirectional experience. As humans domesticate rabbits, so do rabbits domesticate their humans. If teleonomy is the apparent purpose in the organization of living systems, then transgenic art suggests a non-utilitarian and more subtle approach to the debate. Moving beyond the metaphor of the artwork as a living organism into a complex embodiment of the trope, transgenic art opens a nonteleonomic domain for the life sciences. In other words, in the context of transgenic art humans exert influence in the organization of living systems, but this influence does not have a pragmatic purpose. Transgenic art does not attempt to moderate, undermine, or arbitrate the public discussion. It seeks to offer a new perspective that offers ambiguity and subtlety where we usually only find affirmative ("in favor") and negative ("against") polarity. "GFP Bunny" highlights the fact that transgenic animals are regular creatures that are as much part of social life as any other life form, and thus are deserving of as much love and care as any other animal.

The present is a selection and montage of some texts of the brazilian transgenic-artist Eduardo Kac, wich can be fully read at his site . Eduardo is Professor of Art and Technology (School of the Art Institute of Chicago).